[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="400"]

A knocked-out German PzKpfw IV tank in a hull-down position, 13 July 1944. Additional info: "A dug-in Panzer IV of the 1/22nd Panzer Regiment, photographed near Lebisey after being knocked out during Operation Charnwood.(Battle for Caen, p. 34, by Simon Trew. ISBN:0-7509-3010-1) Charnwood Category:Military history of Normandy Category:World War II operations and battles of Europe Category:Battles and operations of World War II Charnwood, Operation Charnwood, Operation Charnwood, Operation (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Operation Goodwood was a Second World War British offensive that took place between 18 and 20 July 1944. British VIII Corps, with three armoured divisions, launched the attack aiming to seize the German-held Bourguébus Ridge, along with the area between Bretteville-sur-Laize and Vimont, while also destroying as many German tanks as possible.

Goodwood was proceeded by preliminary attacks dubbed the Second Battle of the Odon. On 18 July, British I Corps conducted an advance to secure a series of villages and the eastern flank of VIII Corps. On VIII Corps's western flank, Canadian II Corps launched a coordinated attack—codenamed Operation Atlantic—aimed at capturing the remaining German-held sections of the city of Caen south of the Orne River.

When Operation Goodwood ended on 20 July, the armoured divisions had broken through the initial German defences and had advanced seven miles before coming to a halt in front of the Bourguébus Ridge, although armoured cars had penetrated further south and over the ridge.

Since 1944, there has been controversy over what the actual objective of the operation was: whether it was a limited attack to secure Caen and pin German formations in the eastern region of the Normandy beachhead, preventing them from disengaging to join the counterattack against the US Operation Cobra, or a failed attempted breakout from the Normandy bridgehead. At least one historian has called the operation the largest tank battle that the British Army has ever fought.

Background

The historic Normandy town of Caen was a D-Day objective for the British 3rd Infantry Division that landed on Sword Beach on 6 June 1944.

[15] The capture of Caen, while "ambitious", has been described by historian L F Ellis as the most important D-Day objective assigned to Lieutenant-General Crocker's I Corps.

[nb 4] Operation Overlord called for Second Army to secure the city and then form a front line from Caumont-l'Éventé to the south-east of Caen, in order to acquire airfields and protect the left flank of the United States First Armywhile it moved on Cherbourg.

[19] Possession of Caen and its surroundings would give Second Army a suitable staging area for a push south to capture Falaise, which could itself be used as the pivot for a swing left to advance on Argentan and then towards the Touques River.

[20] The terrain between Caen and Vimont was especially promising, being open, dry and conducive to swift offensive operations. Since the Allied forces greatly outnumbered the Germans in tanks and mobile units, transforming the battle into a more fluid fast-moving battle was to their advantage.

[21]Hampered by congestion in the beachhead that delayed the deployment of its armoured support and forced to divert effort to attacking strongly held German positions along the 9.3-mile (15.0 km) route to the town, the 3rd Division was unable to assault Caen in force and was stopped short of the outskirts.

[22] Follow-up attacks were unsuccessful as German resistance solidified; abandoning the direct approach, Operation Perch—a pincer attack by I and XXX Corps

[23]—was launched on 7 June, with the intention of encircling Caen from the east and west.

[24] I Corps, striking south out of the Orne bridgehead, was halted by the 21st Panzer Division,

[25] and the attack by XXX Corps bogged down in front of Tilly-sur-Seulles, west of Caen, in the face of stiff opposition from the Panzer Lehr Division.

[24] In an effort to force Panzer Lehr to withdraw or surrender

[26] and thereby keep operations fluid, the 7th Armoured Division pushed through a gap in the German front line and tried to capture the town of Villers-Bocage in the German rear.

[27] The resulting day long battle saw the vanguard of the 7th Armoured Division withdraw from the town,

[28] but by 17 June Panzer Lehr had themselves been forced back and XXX Corps had taken Tilly-sur-Seulles.

[29] The British were forced to abandon plans for further offensive operations, including a second attack by the 7th Armoured Division,

[30] when on 19 June a severe storm descended upon the English Channel. The storm, which lasted for three days, significantly delayed the Allied build-up.

[31] Most of the landing craft and ships already at sea were driven back to ports in Britain; towed barges and other loads (including 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of floating roadways for the Mulberry harbours) were lost; and 800 craft were left stranded on the Normandy beaches until the next high tides in July.

[32]Having taken a few days to make good the deficiencies caused by the storm, on 26 June the British launched Operation Epsom. The newly arrived VIII Corps, under Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O'Connor, was to strike to the west of Caen south across the Odon and Orne rivers, capture an area of high ground near Bretteville-sur-Laize, and thus encircle the city.

[33] The attack was preceded by Operation Martlet, the aim of which was to secure VIII Corp's flank by capturing high ground on the right of the axis of advance.

[34] Although the Germans managed to contain the offensive, to do so they had been obliged to commit all their available strength

[35] including two panzer divisions just arrived in Normandy

[36] and earmarked for a planned offensive against British and American positions around Bayeux.

[37] Several days later Second Army made another bid to gain possession of Caen, this time by frontal assault, codenamed Operation Charnwood.

[38] As a prelude Operation Windsor, a postponed attack to capture the airfield at Carpiquet just outside Caen, was mounted.

[39] By 9 July Charnwood had succeeded in taking northern Caen up to the Orne and Odon rivers,

[38] but German forces retained possession of the south bank and a number of important locations including the Colombelles steel works, whose tall chimneys gave them commanding observation posts overlooking the area.

Allies

On 10 July, General Bernard Montgomery, the commander of all the Allied ground forces in Normandy, held a meeting at his headquarters with his army commanders, Lieutenant-Generals Miles Dempsey (British Second Army) and Omar Bradley (United States First Army). They discussed 21st Army Group's employment

[42] following the conclusion of Operation Charnwood and the failure of First Army's initial breakout offensive.

[43] Montgomery approved Bradley's suggestion for a new offensive codenamed Operation Cobra, a second American breakout attempt to be launched by First Army on 18 July.

[44] To facilitate Cobra Montgomery ordered Dempsey to "go on hitting: drawing the German strength, especially the armour, onto yourself - so as to ease the way for Brad".

[42]In early July, Montgomery had been informed by the Adjutant-General to the Forces, Ronald Adam, that, due to a worsening manpower shortage in Britain, sufficient replacements to maintain his infantry strength would not be forthcoming.

[45] This led Dempsey

[nb 5] to propose an attack comprised solely of armoured divisions, a concept that violated Montgomery's personal policy of never employing such an unbalanced force.

[47] However, tanks were one commodity with which the British were plentifully supplied.

[48] By mid-July, Second Army had 2,250 medium tanks and 400 light tanks in the bridgehead,

[49] of which 500 were in reserve to replace losses.

[50] These were organised into three armoured divisions

[nb 6] and seven independent armoured / tank brigades.

[nb 7]At 10:00 on 13 July, Dempsey met with three of his five corps commanders

[nb 8] to discuss his idea. Later that day, the first written order for Operation Goodwood—named after the Glorious Goodwood race meeting

[59]—was issued.

[60] This document contained only preliminary instructions and the operation's general intentions; it was intended mainly to stimulate detailed planning and alterations were expected.

[61] In addition to Second Army's staff, the order was sent to senior planners in the United Kingdom so that air support for the operation could be secured.

[62]When VIII Corps had first assembled in Normandy in mid-June, it was suggested that the corps be used to attack out of the Orne bridgehead in an attempt to outflank Caen from the east. However this offensive, codenamed Operation Dreadnought, was cancelled when Dempsey and O'Connor made pessimistic assessments to Montgomery regarding the difficulties involved in such an undertaking.

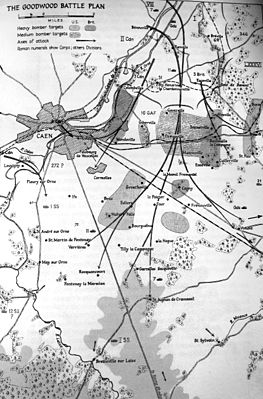

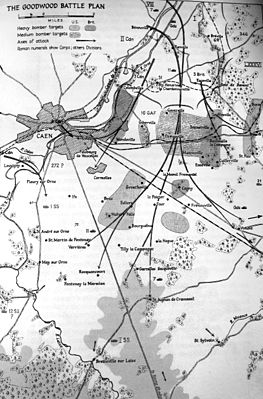

[nb 9] In Goodwood's outline plan, VIII Corps, with three armoured divisions, would now strike south out of the Orne Bridgehead.

[61] The 11th Armoured Division was to advance south-west over the Bourguébus Ridge and the Caen-Falaise road, aiming for Bretteville-sur-Laize. The Guards Armoured Division was to push south-east to capture Vimont and Argences, and 7th Armoured Division, starting last, was to aim south for Falaise itself. The 3rd Infantry Division, supported by elements of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, was to secure VIII Corps's eastern flank by capturing the area around Émiéville, Touffréville and Troarn.

[64] Simultaneously II Canadian Corps would launch a supporting attack on VII Corps's western flank. Codenamed Operation Atlantic, the Canadian offensive was intended to liberate Caen south of the Orne river.

[65] The British and Canadian operations were tentatively scheduled for 18 July, Bradley's estimate for Cobra's start date having been pushed back by two days to enable his US First Army to secure its start line around Saint-Lô.

[66][67]

Detailed planning for Operation Goodwood began on Friday 14 July,[68] but the next day Montgomery issued a written directive ordering Dempsey to make the operation less ambitious. It was to be changed from a "deep break-out" to a "limited attack".[69] Anticipating that the Germans would be forced to commit their armoured reserves rather than risk a massed British tank breakthrough,[70] Dempsey's force was instructed to "engage the German armour in battle and 'write it down' to such an extent that it is of no further value to the Germans". He was to take any opportunity to improve Second Army's position—the orders stated that "a victory on the eastern flank will help us to gain what we want on the western flank"[71]—but not to endanger its role as a "firm bastion" on which the success of the forthcoming American offensive would depend.[72] The objectives of Dempsey's three armoured divisions were rewritten accordingly. They were now only to "dominate the area Bourguébus-Vimont-Bretteville", although it was intended that "armoured cars should push far to the south towards Falaise, spread[ing] alarm and despondency". VIII Corps's objective was changed too, from a wide punch south towards Falaise to a limited thrust to the southwest of Caen. The objectives for II Canadian Corps remained largely unaltered and it was stressed that these were vital. Only following their achievement would VIII Corps "'crack about' as the situation demands".[71]

The 11th Armoured Division was assigned to lead the advance

[73] and was tasked with screening Cagny

[74] and capturing Bras, Hubert-Folie, Verrières and Fontenay-le-Marmion.

[73] Its armoured brigade was to bypass the majority of the German-held villages in its operational area, leaving them to be dealt with by follow-up waves.

[75] The division's infantry component, the 159th Infantry Brigade, was initially to act independently of the rest of the division and capture Cuverville and Démouville.

[76] The Guards Armoured Division, advancing behind the 11th Armoured Division,

[73] was to capture Cagny

[74] and Vimont. Starting last, the 7th Armoured Division was to move south beyond the Garcelles-Secqueville ridge. Further advances by the armoured divisions were to be conducted only on Dempsey's order.

[69] II Canadian Corps's detailed orders were issued a day later. The corps was to first liberate Colombelles and the remaining portion of Caen, and then to hold itself in readiness to move on the strongly held Verrières Ridge.

[77] If the German front collapsed a deeper advance would be considered.

[69]Second Army's intelligence services had formed a good estimate of the opposition Operation Goodwood was likely to face, although the German positions beyond the first line of villages had to be inferred mainly from inconclusive air reconnaissance.

[41] The German defensive line was believed to consist of two belts up to four miles deep.

[78] Aware that the Germans were expecting a large attack out of the Orne bridgehead,

[79]the British initially anticipated meeting resistance from the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division bolstered by SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment 25 of the12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend.

[80] Signals intelligence ascertained that the 12th SS Panzer Division had been moved into reserve, and although it was slow to discover that SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment 25 was not with the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, having also been placed into reserve, this oversight was rectified before 18 July.

[80] Battle groups of the 21st Panzer Division, with around 50 Panzer IV tanks and 34assault guns, were expected near Route nationale 13.

[80] The 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler was identified in reserve with an estimated 40 Panther tanks and 60 Panzer IV's,

[nb 10] and the presence of two heavy tank battalions equipped with Tiger tanks

[disambiguation needed] was established.

[nb 11] German armoured strength was estimated at 230 tanks

[81] and artillery strength at 300 field and anti-tank guns.

[nb 12] Second Army believed that 90 of these guns were in the centre of the battle zone, 40 on the flanks, and a further 20 defending the Caen-Vimont railway line.

[80] The British had also located a German gun line on the Bourguébus Ridge, but its strength and gun positions were unknown.

In an attempt to mask the operation's objectives, Second Army initiated a deception plan that included diversionary attacks launched by XII and XXX Corps.[83] Dempsey's three armoured divisions moved to their staging positions west of the Orne only at night and in radio silence,and artillery fire was used to mask the noise of the tank engines.[84] During the hours of daylight all efforts were made to camouflage their new positions.

For artillery support, Goodwood was allocated 760 guns

[nb 13] with 297,600 rounds.

[nb 14] Prior to the assault these were to attempt to suppress German anti-tank,

[87] anti-aircraft

[88] and field artillery positions, and during the assault would provide the 11th Armoured Division with a rolling barrage. They would also assist the attacks launched by the 3rd Infantry and 2nd Canadian Infantry Divisions and, throughout the operation, fire on targets as requested.

[87] Additional support would be provided by three ships of the Royal Navy,

[nb 15] whose targets were German gun batteries located near the coast in the region of Cabourg and Franceville.

[85]Augmenting the preliminary artillery bombardment, 2,077

[nb 16] heavy and medium bombers of the Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) would attack in three waves, in the largest air raid launched in direct support of ground forces in the campaign so far.

[90] Speed was an essential part of the Goodwood battle plan and it was hoped that the aerial bombardment would pave the way for the 11th Armoured Division to rapidly secure the Bourguébus Ridge.

[75] Dempsey believed that if the operation were to succeed, his tanks would need to be on the ridge by the first afternoon.

[91] He therefore cancelled a second attack by heavy bombers scheduled for the first afternoon. Although this was to be in direct support of the advance towards the ridge

[85] he was concerned that the 11th Armoured Division should not be delayed waiting for the strike.

[91]Close air support for Goodwood would be provided by No. 83 Group RAF, which was tasked with neutralising German positions on the flanks of VIII Corps' planned advance and strong points such as the village of Cagny, attacking German gun and reserve positions, and the interdiction of German troop movement.

[89] Each of VIII Corps's brigade headquarters was allocated a Forward Air Control Post to assist with coordinating air support.

[92]The engineering resources of Second Army, I and VIII Corps, and the divisional engineers were put to work between 13 July and the evening of 16 July building six new roads from west of the Orne River to the start lines east of the river and the Caen Canal.

[93] Engineers from I Corps strengthened existing bridges and built two new sets of bridges across the Orne and the canal.

[94] They were further tasked with constructing another two sets of bridges by the end of the operation's first day.

[95][nb 17] II Canadian Corps planned to construct up to three bridges across the Orne as soon as the opportunity presented itself, giving I and VIII Corps exclusive access to the river and canal bridges north of Caen.

[94] Engineers from the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, with a small detachment from the 3rd Infantry Division, were ordered to breach the German minefield in front of the Highland Division's position. This was largely accomplished during the night of 16–17 July when they cleared and marked 14 gaps.

[97] By the morning of 18 July, 19 40-foot (12 m) wide gaps had been completed,

[98] each allowing one armoured regiment to pass through at a time.

[nb 18]The 11th Armoured Division's infantry brigade, with the divisional and 29th Armoured Brigade's headquarters, crossed into the Orne bridgehead during the night of 16–17 July. The rest of the division followed the next night.

[99] The Guards and 7th Armoured Divisions were held west of the river until the operation began.

[84] As the final elements of the 11th Armoured Division moved into position and VIII Corps's headquarters took up residence in Bény-sur-Mer additional gaps in the minefields were blown, the forward areas were signposted, and routes to be taken marked with white tape.

[100]GermansThe Germans considered the Caen area to be the linchpin of their position in Normandy and were determined to maintain a defensive arc from the English Channel to the west bank of the Orne.

[101] On 15 July German military intelligence warned Panzer Group West that from 17 July onwards a British attack out of the Orne bridgehead was likely. It was thought that the British would push south-east towards Paris.

To meet this threat, General Heinrich Eberbach, the commanding officer of Panzer Group West, designed a defensive plan, with its details worked out by his two corps and six divisional commanders.

[102] A belt of at least 10 miles (16 km) depth

[81][103] was constructed, organised into four successive lines.

[104] Villages within the belt were fortified and anti-tank guns emplaced along its southern and eastern edges.

[81] To allow their tanks to move freely within the belt, the Germans decided not to establish anti-tank minefields between each defensive line.

On 16 July, several intelligence-gathering flights were mounted over the British front, but most of these were driven off by anti-aircraft fire.

[105] However, as darkness fell, camera-equipped aircraft managed to bring back photographs taken by the light of dropped flares that revealed a one-way flow of traffic over the Orne and into the British bridgehead.

[82] Further confirming the suspicion that preparations for an offensive were underway, later that same day a British reconnaissance Supermarine Spitfire was shot down over German lines while photographing defences; British artillery and fighters attempted to destroy the crashed aircraft but without success.

LXXXVI Corps, heavily reinforced by artillery,[106] held the front line. Its 346th Infantry Division was dug in between the coast to the north of Touffreville, while the battered 16th Luftwaffe Infantry Division held the next section from Touffreville to Colombelles. Kampfgruppe von Luck, a battle group formed around the 21st Panzer Division's 125th Panzergrenadier Regiment, was placed behind these forces with around 30 assault guns. The 21st Panzer Division's armoured elements, reinforced with the 503rd Heavy Panzer Battalion, which included ten King Tigers,[107] were northeast of Cagny in a position to support von Luck's men and to act as a general reserve,[108] while the rest of the division's panzergrenadiers, with towed anti-tank guns andassault guns, were dug in amongst the villages of the Caen plain.[109] 21st Panzer's reconnaissance and pioneer battalions were positioned on the Bourguébus Ridge to protect the corps's artillery.[91] This consisted of around 48 field and medium guns with an equal number of Nebelwerfer rocket launchers. In total, LXXXVI Corps had 194 artillery pieces, 272 Nebelwerfers,[91] and 78 anti-aircraft and anti-tank 88 mm guns available. One battery of four 88 mm anti-aircraft guns, from the 2nd Flak-Sturm Regiment, was positioned in Cagny,[91] while in the villages along the Bourguébus Ridge there was a screen of 44 88 mm anti-tank guns from the 200th Tank Destroyer Battalion.[107][nb 19] However, the majority of LXXXVI Corps's guns were sited beyond the ridge covering the Caen-Falaise road.[91][110]

Facing Caen to the west of the Caen-Falaise road was the I SS Panzer Corps. On 14 July, elements of the 272nd Infantry Division took over the defence of Vaucelles from the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, who moved into local reserve between the village of Ifs and the east bank of the Orne. The following day the 12th SS Panzer Division was placed in

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) reserve to rest and refit,

[111] and—on Hitler's orders—to be in a position to meet a feared second Allied landing between the Orne and Seine rivers.

[112] The division's artillery regiment and anti-aircraft battalion remained behind to support the 272nd Infantry Division, and two battlegroups were detached from the division.

Kampfgruppe Waldmüller was moved close to Falaise and

Kampfgruppe Wünsche to Lisieux, 40 kilometres (25 mi) east of Caen.

[111] Although

Kampfgruppe Waldmüller was later ordered to rejoin the rest of the division at Lisieux, on 17 July Eberbach halted this move.

[79]Preliminary operations

Main article: Second Battle of the Odon

Shortly after the capture of northern Caen during Operation Charnwood, the British mounted an unsuccessful raid against the Colombelles steelworks complex to the northeast of the city. The factory area remained in German hands, its tall chimneys providing observations posts that overlooked the Orne bridgehead. At 01:00 on 11 July, elements of the 153rd (Highland) Infantry Brigade, supported by Sherman tanks of the Royal Armoured Corps's 148th Regiment, moved against the German position.

[42] The intention was to secure the area only long enough for troops from theRoyal Engineers to destroy the chimneys before pulling back.

[113] However, at 05:00 the British force was ambushed by Tiger tanks and after the loss of nine tanks was forced to withdraw.

[42]

While planning and preparation for Goodwood was underway, Second Army launched two preliminary operations. According to Montgomery, their purpose was to "engage the enemy in battle unceasingly; we must 'write off' his troops; and generally we must kill Germans". Historian Terry Copp identifies this as the moment where the Normandy campaign became a battle of attrition; one that Montgomery did his best to ensure the Germans would not win.[114]

was launched by XII Corps during the evening of 15 July.

[nb 20][116] Greenline's objectives were twofold: to convince the German command that the forthcoming major British assault would be launched west of the Orne though the positions held by XII Corps;

[83] and to tie down the9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions so that they could not later be relocated to oppose either Goodwood or Operation Cobra.

[115] Supported by 450 guns, the British attack made use of "artificial moonlight"

[nb 21] and started well despite disruption caused by German artillery fire. By dawn XII Corps had captured several of its objectives including the important height of Hill 113, although the much-contested Hill 112 remained in German hands. Committing the 9th SS Panzer Division, the Germans managed by the end of the day to largely restore their line, although a counter-attack against Hill 113 was unsuccessful.

[117] Renewed attacks the following day by XII Corps gained no further ground, so during the evening of 17 July the operation was closed down and the British force on Hill 113 withdrawn.

Operation Pomegranate started on 16 July, one day after Greenline.[ XXX Corps was to capture several important villages.[119] On the first day British infantry seized a key objective and took 300 prisoners but the next day saw heavy and inconclusive fighting on the outskirts of Noyers-Bocage.[120] Elements of the 9th SS Panzer Division were committed to the village's defence; although the British took control of the railway station and an area of high ground outside the village, Noyers-Bocage itself remained in German hands.[119]

These two operations cost Second Army 3,500 casualties

[6] for no significant territorial gains, but Greenline and Pomegranate were strategically successful. Reacting to the developing threats in the Odon Valley, the Germans not only retained the 2nd Panzer and 10th SS Panzer Divisions in the front line but also recalled the 9th SS Panzer Division from Corps reserve.

[83][119][121] They suffered around 2,000 casualties; the heavy losses on both sides prompted Terry Copp to call the fighting "one of the bloodiest encounters of the campaign".

During the late afternoon of 17 July a patrolling British Spitfire fighter aircraft spotted a German staff car on the road near the village of Sainte-Foy-de-Montgommery. The fighter made a strafing attack driving the car off the road. Among its occupants was Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the commander ofArmy Group B, who was seriously wounded leaving Army Group B temporarily leaderless.